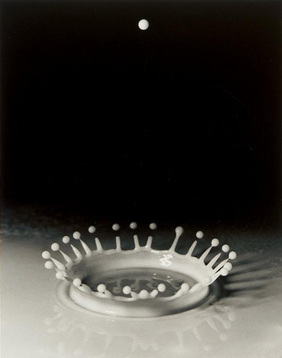

Doc Edgerton's iconic milk drop coronet.

Doc Edgerton's iconic milk drop coronet. The Edgertronic high-speed camera we are using on Mission 31 has never been used underwater. It just came out five weeks ago, and the underwater housing that Sexton Corporation customized for us (for the camera) arrived the eve of Liz and my Aquarius splashdown.

On land, MIT's "Doc" Edgerton revolutionized how we view motion. His iconic image of a milk drop, for example, shows the coronet-shaped structure formed the instant a drop hits liquid. It's fascinating that we “see” this seemly mundane phenomenon daily, yet its true majesty is never visible to the naked eye without the incredible speed of a camera to take images at fractions of a second.

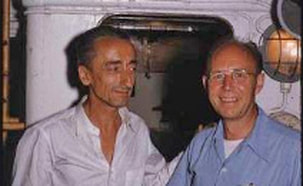

Back in the 1950s, Jacques Cousteau and Doc Edgerton ("Papa Flash," as Cousteau called him) were fast friends. Jacques was the intrepid explorer and Edgerton the MIT tech whiz who developed special technologies that helped locate, capture and convey the glory of Jacques’ underwater discoveries. Now in 2014, the 50th anniversary of Jacques Cousteau’s Conshelf II underwater habitat expidition, the legacies of these two great pioneers are united once again on Mission 31 to hopefully convey some of the wonders we're still discovering undersea by testing the limits of new underwater imaging technology.

Our work with the Edgertronic camera on Mission 31 is capturing motion previously observed, but never fully visible, similar to the milk drop coronet phenomenon. Depending on the chosen resolution, this camera is capable of 500 frames per second at high resolution, and 18,000 (eighteen thousand!) frames per second at its lowest resolution. We're attempting to capture behaviors of undersea life with this incredible technology, and hope to ultimately capture the unique feeding behavior of the Goliath grouper (video not captured with Edgertronic).

The camera is tricky to use underwater. Adequate lighting is critical for the camera because the shutter is only open for fractions of a second, and good lighting is scarce to nonexistent undersea. In addition, setup takes about a half hour of sea time, and then another of hour of shooting time with someone providing computerized feedback from the dry habitat. (Liz wrote a blog post about the set-up process required.) We could really use more time!

The videos we are capturing are amazing. We are seeing the super-fast movements of sea creatures on a whole new time scale, movements that are impossible to comprehend with the naked eye. It’s mind-blowing to me to see nature working at this level. Several days ago I posted a short video of a yellow-headed jawfish and Liz posted a video of a manits shrimp striking a goby. Hopefully we'll post more in the coming days. Someday, I'd love to frame these images and put them with the videos in a museum: The Underwater World through Edgerton's Eyes.

On land, MIT's "Doc" Edgerton revolutionized how we view motion. His iconic image of a milk drop, for example, shows the coronet-shaped structure formed the instant a drop hits liquid. It's fascinating that we “see” this seemly mundane phenomenon daily, yet its true majesty is never visible to the naked eye without the incredible speed of a camera to take images at fractions of a second.

Back in the 1950s, Jacques Cousteau and Doc Edgerton ("Papa Flash," as Cousteau called him) were fast friends. Jacques was the intrepid explorer and Edgerton the MIT tech whiz who developed special technologies that helped locate, capture and convey the glory of Jacques’ underwater discoveries. Now in 2014, the 50th anniversary of Jacques Cousteau’s Conshelf II underwater habitat expidition, the legacies of these two great pioneers are united once again on Mission 31 to hopefully convey some of the wonders we're still discovering undersea by testing the limits of new underwater imaging technology.

Our work with the Edgertronic camera on Mission 31 is capturing motion previously observed, but never fully visible, similar to the milk drop coronet phenomenon. Depending on the chosen resolution, this camera is capable of 500 frames per second at high resolution, and 18,000 (eighteen thousand!) frames per second at its lowest resolution. We're attempting to capture behaviors of undersea life with this incredible technology, and hope to ultimately capture the unique feeding behavior of the Goliath grouper (video not captured with Edgertronic).

The camera is tricky to use underwater. Adequate lighting is critical for the camera because the shutter is only open for fractions of a second, and good lighting is scarce to nonexistent undersea. In addition, setup takes about a half hour of sea time, and then another of hour of shooting time with someone providing computerized feedback from the dry habitat. (Liz wrote a blog post about the set-up process required.) We could really use more time!

The videos we are capturing are amazing. We are seeing the super-fast movements of sea creatures on a whole new time scale, movements that are impossible to comprehend with the naked eye. It’s mind-blowing to me to see nature working at this level. Several days ago I posted a short video of a yellow-headed jawfish and Liz posted a video of a manits shrimp striking a goby. Hopefully we'll post more in the coming days. Someday, I'd love to frame these images and put them with the videos in a museum: The Underwater World through Edgerton's Eyes.

| Fellow aquanaut Liz Magee from Northeastern's Three Seas Program with the Edgertronic camera as we work together to capture images of sea life. | Setting-up the Edgertronic camera. This image is from Matt Ferraro, a fellow aquanaut and filmmaker from Changing Tides Media with over 15 years of experience. |

Update 6/28/14: Here's a video from Mission 31 about our work with the camera underwater.

| |

We also continue work on other of Mission 31 research projects, such as zooplankton collection and sea sponge identification and sampling for Northeastern's Ocean Genome Legacy project.

More blog at:

- What's Mission 31 About? This is Worth the Watch and

- Stunning Views of Life in the Sea, which shows some behind the scenes photos of setting up work with the Edgertronic camera.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed