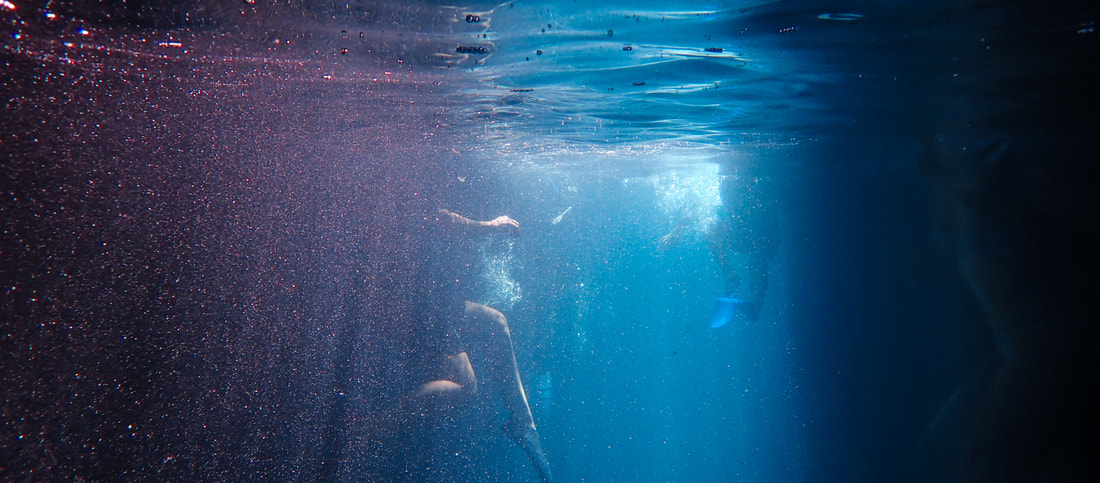

It’s not sharks or barracuda. (Image Source: Pexels)

I originally wrote and published the following piece for LinkedIn; comment and join the conversation here! It was shared by X - The Moonshot Factory on World Conservation Day 2020. If you've followed my other posts recently you might be thinking "this gal is obsessed with Dr Ayana Elizabeth Johnson". And yea, it's true. We had the pleasure of hosting Dr Johnson last month at X, which gave me the perfect excuse to catch up on her writings, and I found them inspiring.

I’ve swam at night with sharks and barracuda, watching these predators up close with awe. I’ve lived underwater, spending 15 full days immersed in the Aquarius undersea lab. I’ve sailed across the Atlantic, losing battery power for navigation tools on the way and nearly running out of food and fuel in the process. Whenever I share these experiences, the most common question I’m asked is, “Weren’t you scared!?”

Yes, I’m scared — but I’m not scared for the reasons people might assume. During years of training, my teams and I considered and practiced how to deal with any imaginable emergency contingency. Before and during missions, we reviewed the risks we faced and implemented plans to mitigate them. Because of all this training, my personal safety doesn’t consume any raw emotional fear at the time of a mission; if it did, I likely wouldn’t join because it would indicate to me that I wasn't prepared sufficiently. Instead, I’m afraid for what the ocean will be able to provide for current and future generations.

My greatest fear is that we’ll destroy marine ecosystems before we know they exist, or before we understand how dependent we are upon them. As I told National Geographic back in 2014, after emerging from more than two weeks conducting research undersea at the Aquarius lab: "I find it incredibly frightening that we have the technology to completely destroy the ocean in my lifetime." What I hope we now find is that we also have the technology to remediate our relationship with the ocean and its incredible resources.

World Conservation Day is a time for us to think critically about the relationship between the ocean, humanity, and technology — especially this year, as we grapple with what we took for granted and what the future holds. COVID-19 has highlighted our relationship to nature like never before. Many of us have never had to think about staying safe while breathing the same air as others, or touching surfaces without disinfecting them, or our place in the ecosystem. Although the precise source of COVID-19 is not yet known, we know infectious disease rates increase as we encroach into — and damage — natural habitats and ecosystems. Likewise, global protests against racial injustice have reinforced how environmental and racial justice are irrevocably linked while showing just how much lasting change needs to happen. Even if that systemic change can be difficult, it’s possible. But if our relationship to the ocean is based in fear and despair, it can be hard to see where the opportunities for change lie — and what levers are within our control.

With that in mind, I’m looking for ways to re-frame my fear of “what do we lose when marine ecosystems are destroyed?” to “what do we gain by living and working in harmony with them?” The ocean has been here far longer than we have, proving its resilience and adaptability to change across millennia. Realistically, while we don’t need to fear the world beneath the waves, we also don’t need to “save the ocean.” Instead, we must work to find ways to live in harmony, sustainably, with the ocean and its complex ecosystems. In the words of Dr Ayana Elizabeth Johnson: “We are overdue for a re-frame, from seeing the ocean as victim or threat, to appreciating it as hero.”

Yes, I’m scared — but I’m not scared for the reasons people might assume. During years of training, my teams and I considered and practiced how to deal with any imaginable emergency contingency. Before and during missions, we reviewed the risks we faced and implemented plans to mitigate them. Because of all this training, my personal safety doesn’t consume any raw emotional fear at the time of a mission; if it did, I likely wouldn’t join because it would indicate to me that I wasn't prepared sufficiently. Instead, I’m afraid for what the ocean will be able to provide for current and future generations.

My greatest fear is that we’ll destroy marine ecosystems before we know they exist, or before we understand how dependent we are upon them. As I told National Geographic back in 2014, after emerging from more than two weeks conducting research undersea at the Aquarius lab: "I find it incredibly frightening that we have the technology to completely destroy the ocean in my lifetime." What I hope we now find is that we also have the technology to remediate our relationship with the ocean and its incredible resources.

World Conservation Day is a time for us to think critically about the relationship between the ocean, humanity, and technology — especially this year, as we grapple with what we took for granted and what the future holds. COVID-19 has highlighted our relationship to nature like never before. Many of us have never had to think about staying safe while breathing the same air as others, or touching surfaces without disinfecting them, or our place in the ecosystem. Although the precise source of COVID-19 is not yet known, we know infectious disease rates increase as we encroach into — and damage — natural habitats and ecosystems. Likewise, global protests against racial injustice have reinforced how environmental and racial justice are irrevocably linked while showing just how much lasting change needs to happen. Even if that systemic change can be difficult, it’s possible. But if our relationship to the ocean is based in fear and despair, it can be hard to see where the opportunities for change lie — and what levers are within our control.

With that in mind, I’m looking for ways to re-frame my fear of “what do we lose when marine ecosystems are destroyed?” to “what do we gain by living and working in harmony with them?” The ocean has been here far longer than we have, proving its resilience and adaptability to change across millennia. Realistically, while we don’t need to fear the world beneath the waves, we also don’t need to “save the ocean.” Instead, we must work to find ways to live in harmony, sustainably, with the ocean and its complex ecosystems. In the words of Dr Ayana Elizabeth Johnson: “We are overdue for a re-frame, from seeing the ocean as victim or threat, to appreciating it as hero.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed